Options Primer

This blog post will provide a primer on options and a few common uses. This topic was requested by a client. Initially I hesitated, given the complexities. Upon further reflection, I decided to proceed with a high-level overview, but also the necessary precautions for anyone considering options and the extra risks, implicit leverage, and unique portfolio and trading considerations relative to stocks or exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

So here goes. “… And hey… let’s be careful out there.” (anyone old enough for Hill Street Blues?)

Here are the option-related topics I will cover:

Option terminology and ability to buy and sell options

Payoff graphs if sell calls or puts

Exchange-traded options and typical features

Three common strategies – covered calls, cash-secured puts, hedging

Selling option premium is NOT free money

CBOE indices and ETFs that capture some of these strategies

Equally important, here are some topics I will not cover since out of scope for this blog but are still important to understand.

Black-Scholes Pricing Model and Put-Call Parity relationships

Using call options vs. buying the underlying stock for leverage

Combinations of options that go by various names, including a “stock repair strategy”

0DTE (zero days to expiration) options; minimal time value with premium gone in a day

Amount of “delta” options can generate with leverage and technical market impacts

Detailed tax treatment of the various strategies

What qualifies for Section 1256 tax treatment resulting in 60/40 long/short-term gains

Special considerations for company issued stock options

The many other topics that an “options discussion” could cover.

Now back to the topics I will cover!

Option terminology and ability to buy and sell options

If you want to do a deep dive, you could purchase the book Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives (9th Edition) by John C. Hull. But since you are on my blog post for a quick hit, you need to be familiar with the two main types of options – a call and a put – and the fact that you can either buy or sell each of these options. Each option references an underlying stock or ETF (or other), has a strike price which drives the value of the option relative to underlying price, and length of time until the option expires (days, weeks, months, years).

Call gives someone the right, but not obligation, to buy a stock at the strike price

Put gives someone the right, but not obligation, to sell a stock at the strike price

Because an option is a right but not an obligation, there is a one-sided payoff. This feature has a value based primarily on the combination of underlying stock, strike price and length of the option and is called the option premium. The interesting thing is you can either buy or sell these options depending on your view and strategy. If you buy, you need the cash to pay the premium; if sell, you receive the premium amount in cash.

If you buy a call or a put, you get to choose whether and when to “exercise the option” and either buy (with a call) or sell (with a put) at the strike price for the underlying stock, regardless of the market price. If the underlying stock price is more favorable then the strike, you can just walk away from the option and transact in the open market if wish. The ability to have this right to walk away is achieved by paying the option premium.

If you sell a call or put, you receive the option premium. In return, for selling calls, you have committed to selling a stock at the strike price if the buyer of the call comes knocking, which they will if the market price is higher than the strike price. For selling puts, you have committed to buying a stock at the strike price if the buyer of the put comes knocking, which they will if the market price is lower than the strike price. Of course, if the buyer of the option does not come knocking, you get to keep the premium.

Payoff graphs if sell calls or puts

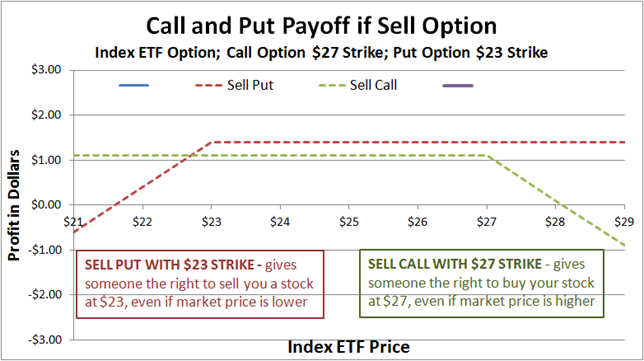

That was enough terminology so let’s now create a picture to help solidify the concept. The graph below shows the payoff profile at expiration for both a call and a put for different market prices relative to a single strike price. Recall you can either buy or sell these options. The graph shows the payoff if you sell these options since those are the main strategies covered in this blog post.

The green dashed line is the payoff for selling a call option with a $27 strike price for an initial option premium of $1.10/share. Because the buyer of that option would go to the open market and buy the stock at a lower price, your payoff is the option premium you keep. If the market price is above the strike, the buyer of that call will come knocking at expiration (let’s ignore dividends) and want to buy the stock at the lower strike prices. Note the payoff remains positive until the market price exceeds the strike + initial premium. In this example losses begin at $28.10 and can go to infinity minus $1.10 if the stock price goes to infinity. This is a very important risk that can be mitigated by using a “covered” strategy (see later).

The red dashed line is the payoff for selling a put option with a $23 strike for $1.40/share. Since the buyer of the put would go to the open market and sell at a higher price above $23, those are scenarios where the payoff is the initial premium. The put buyer will come knocking at expiration (ignore dividends) if the market price is below $23 – they can sell to you at $23 – and you begin losing money at a price below $21.60 ($23 - $1.40 premium). In this example the most you can lose is $21.60 (strike price minus premium).

To visualize the payoff for buying a call or put, just flip the graphs and start at negative the premium amounts. If you bought the call, your payoff at expiration is -$1.10 at market prices below $27, hitting $0 at $28.10 and rising from there. At $30 market price for example, the payoff would be $1.90 ($30 minus $27 minus $1.10). If you bought a put, payoff is -$1.40 for prices above $23, hits $0 at $21.60 and goes up from there.

I mentioned the payoff “at expiration”. The value of the option before expiration will move in value, not only due to underlying market price but also changes in implied volatility of the underlying stock which drive the price of the option premium. One common implied volatility gauge is the VIX which captures 30-day volatility on the S&P500. Further details are beyond the scope of this blog but recognize the value of the option before expiration will move around based not only on underlying price changes, but also implied volatility, time passing, and dividend activity among other things.

Exchange-traded options and typical features

Before talking about a few common strategies, I will briefly discuss some common features of exchange-traded options. This differs from over-the-counter options where the terms can be customized.

Exchange traded options have set expiration dates. For monthly options it is the third Friday of the month. Depending on the underlying stock (or ETF, etc.) they typically go out 2-3 months, then quarterly for a year, then maybe an annual expiration 1 and 2 years out. There are also weekly options for some stocks and even options with less than 1 day to expiration (be careful). The strike prices can be down to each $ above and below current levels for many points. Large price stocks may have $5 increments and smaller priced stocks may have down to $0.50. The option is quoted per share but 1 contract captures 100 shares of underlying. So if a particular option premium is $0.75/share and you trade one contract, will need $75 for one contract. These contracts are American-style options, which allow the owner of the option to exercise anytime they wish before expiration. The other type is European-style option which only can be exercised on expiration date.

Not all stocks and ETFs have options. Some that do are not that liquid and the bid/ask can be very wide. The most liquid options may be quoted a penny or two bid/ask while less liquid can be a dollar or two (or more) wide. Be sure to use limit orders on most.

Three common strategies – covered calls, cash-secured puts, hedging

Now that we laid the groundwork, let’s describe - and show a graph – for three common option strategies that are considered more conservative, relative to what can be done with options. The main reason I consider them more conservative is because you also hold either the related stock or cash of the option and therefore not exposed to an unexpected option exercise where cash is needed quickly.

Covered Calls

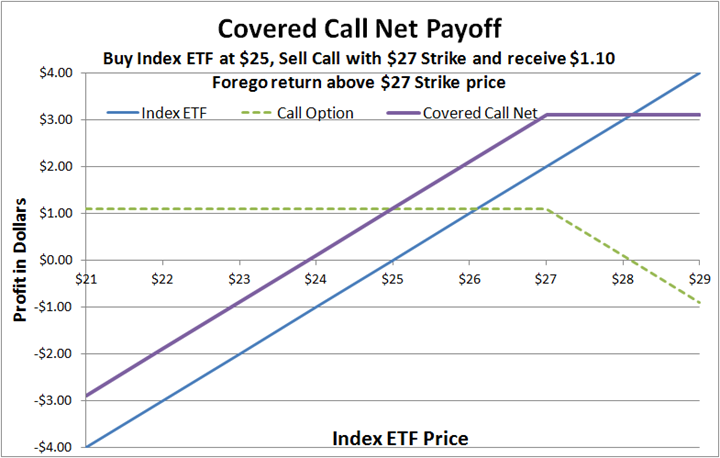

This strategy starts with already owning the underlying stock or ETF as part of a diversified portfolio. Your gain or loss potential can go up or down as the underlying price moves. You could then sell a call option that references this underlying holding (thus “covered”) with a strike price above the current market level and collect the option premium. If the underlying stock or ETF price stays below the strike price you have enhanced the return on the combined holding. However, if the underlying price goes above the strike, you must sell your position at the strike price, even though the market price is higher. The higher the strike price and shorter time to option expiry will result in lower option premium. Using real-time pricing and a robust trading tool or custom-built spreadsheet, one can look at these trade-offs and resulting option premium on an annualized basis to determine best option contract for the investor’s view. Two quick tips - option’s delta is approximately equal to probability of strike being hit at expiration and annualizing option premium is helpful for context.

The graph below visualizes the payoff of this combined holding. The blue line is the payoff of the underlying stock or ETF, the green dashed line is payoff of call option sold, and the purple line shows the combination of the two. Note how the purple line flattens out above the strike as the price of each offset. Having the underlying stock or ETF mitigates the risk of unlimited losses if selling a call only without the underlying. This also means you are capping your gains at the strike prices + option premium. Another tip – choose the strike and maturity so the probability of being exercised is in the 30’s% or lower.

Cash Secured Puts

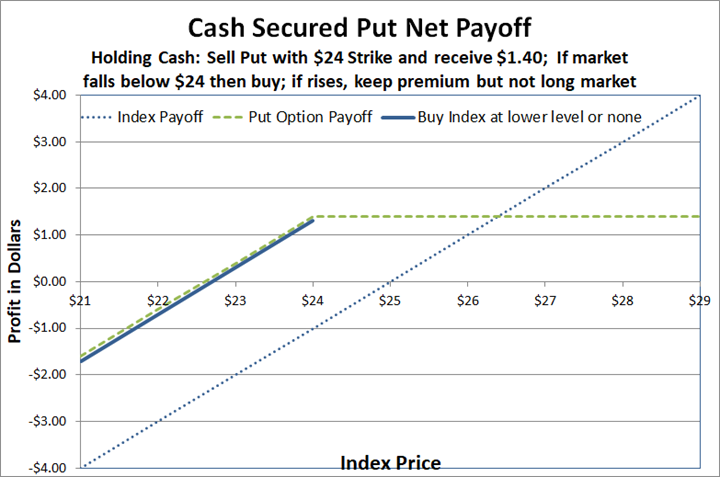

This strategy starts with holding cash and waiting for the price to fall on a stock or ETF before buying. You could just hold the cash in a money market and wait, or sell a put option that references the underlying stock or ETF want to buy at a strike price willing to buy and collect the option premium. Note the cash could not be in a money market if want a true cash-secured put. If the underlying stock or ETF price stays above the strike price you keep the premium but never purchase the stock or ETF. However, if the underlying price goes below the strike, you must buy the stock or ETF at the strike price, even if the market price is lower.

The graph below visualizes the payoff of this potential holding. The blue dashed line is the payoff if you simply purchased the stock or ETF at current levels, the green dashed line is payoff of put option sold, and the blue solid line shows the payoff if you take possession of the stock or ETF from the put being exercised against you and the cash used to purchase at strike price. Note selling the put lowers your purchase price by the option premium IF the stock falls, but also note you never get long the stock or ETF if the price keeps rising (but you keep the premium), so be sure overall portfolio intentions are ok with this scenario.

Portfolio Hedge with Puts

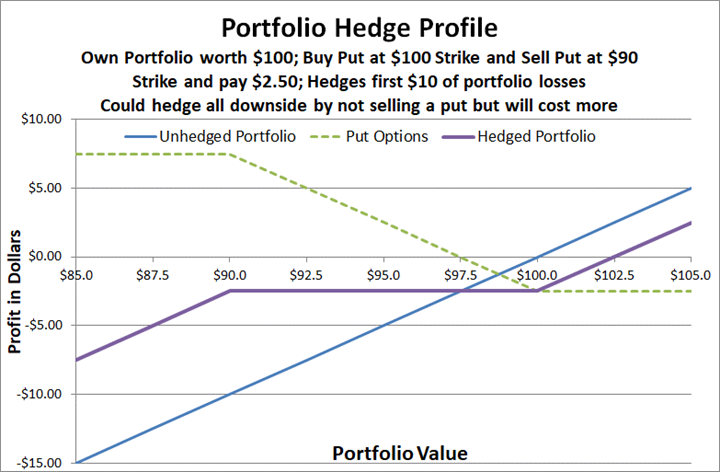

This strategy starts with already owning the underlying stock or ETF as part of a diversified portfolio. Your gain or loss potential can go up or down as the underlying price moves. To protect against losses, you could buy a put option that references this underlying holding with a strike price where you want protection from losses to begin. Since buying the put, you will have to pay the option premium for this protection. If the underlying stock or ETF price falls below the strike price, the put option will protect you against losses below that level. However, if the underlying price stays above the strike, your portfolio will continue to enjoy the upside gains, but portfolio return will be lower by the option premium. One way to reduce the option premium in exchange for less protection is to stop the protection by selling a put option at a lower strike price where protection will stop, using the same underlying and maturity of the option. Adding this extra selling of put (combo called a put spread) requires margin authority and higher level option approval, but is an efficient way to hedge a portion of the downside. You typically set the initial strike maybe 2-5% below current levels and use longer maturity options, depending on your views and potential catalyst for hedging need.

The graph below visualizes the payoff of this portfolio hedge. The blue line is the payoff of the underlying portfolio and the right half of the green dashed line is payoff of the higher strike put option purchased. The left part of the green dashed line is payoff if also sold a put option at the lower strike price which offset the other protection. The purple line shows the combination of the portfolio and options. Note how the purple line continues to grow if the underlying price grows, but is lowered by the net option premium. The portfolio losses are limited between the two strike prices, then resumes again below the lower strike price.

Selling option premium is NOT free money

Before you get too excited about the idea of selling option premium to pick up the “free money”, be aware of the concept of total return = income + capital gains/losses. The perma-bull may say that stock returns are always positive so not to worry, but recognize the option can also generate capital losses. This is seen in the “covered calls” graph where the green dashed line (call option payoff) begins to turn negative. The good news is the combined stock + option (purple line), even though flat, was positive. So yes you get the option premium gain, and the underlying stock gain up to the strike price, but don’t assume you will always keep all the option premium.

CBOE indices and ETFs that capture some of these strategies

Just like the S&P 500 index is a convenient way to see the return and risk characteristics of owning that type of portfolio, there are also indices for different options strategies published by the Chicago Board Option Exchange (CBOE). While the combination of strike price and option maturity must be standardized for the index construction, and no subjective timing of entering the option based on underlying stock price, the indices provide a useful comparison vs. the same portfolio without using the options. Here is a link to the CBOE site. It is instructive to compare the unhedged S&P500 return (SPY) to the following three indices:

- 2% OTM BuyWrite (BXY) will be close to replicating the covered calls

- 2% OTM PutWrite (PUTY) will be close to replicating the cash secured puts

- 5% Put Protection (PPUT) will be somewhat similar to hedging but does NOT include the lower strike put selling

There are also ETFs that capture the covered call strategy. Like all ETF investments, it is important to understand the underlying risk exposure in the ETF, then with the added layer of complexity as to what type of covered call strategy is added – how tight the strikes are, typical length of option, track record of manager. The riskier the underlying exposure, the higher the implied volatility and potential added option premium, but remember also those potential higher expected losses when exercised against you. But if you understand and like the ETF strategy, it is an “easy button” over managing an option overlay strategy.

There, I made it! This was a longer blog post but necessary given the topic at hand. View this post as only a very preliminary overview of option use and if you are interested, I encourage much further reading and study before employing any of these strategies in your portfolio.

“… And hey… let’s be careful out there.”

Have questions? Reach out! We're happy to help.

Posted by Kirk, a fee-only financial advisor who looks at your complete financial picture through the lens of a multi-disciplined, credentialed professional. www.pvwealthmgt.com