The Good, the Great and the Ugly of the SECURE Act

Last month I summarized 10 major changes passed in the SECURE Act in late 2019. In this post I take a deeper dive into three of them impacting people at different phases of life. And with a nod to the classic films once upon a time, the changes I discuss are good, great and downright ugly.

The Good: 529 funds (up to $10,000) can be used to pay off student loans – but watch state rules.

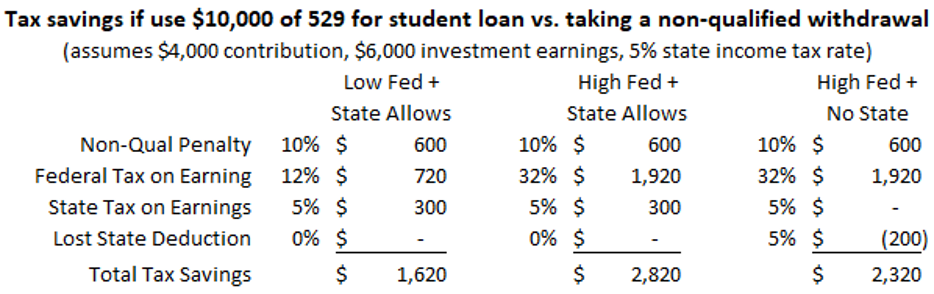

Before the SECURE Act, qualified educational expenses that received tax benefits of 529 plans did not include paying off student loans. Now up to $10,000 in total per beneficiary (not annually or the total loan) can be used to pay off student loans. This is a nice alternative to shifting excess funds to another sibling if a loan exists and have future saving capacity. And if your state allows for loans (not all do) and contributions are state-tax deductible (many are for in-state plans), this provides a discount on $10,000 of the student loan equal to your state tax rate. A final benefit is allowing any extra grandparents’ funds to be shifted into years beyond applying for financial aid (3rd year of school and later).

Before you pooh-pooh this benefit, don’t forget not only does this allow you to avoid ordinary income tax (yes ordinary, NOT capital gains) on investment earnings, you also avoid the 10% penalty for non-qualified expenses. Currently not all states allow this as a qualified withdrawal (Illinois does NOT yet) and you may have to repay any state tax deduction on the original contribution if your state allowed. However, as this example shows it still is worthwhile if the 529 includes a large amount of investment earnings if it was opened at a young age.

The Great: Retirees can wait until age 72 before beginning Required Minimum Distributions (RMD). Note if you were 70.5 on 12/31/2019 then continue with old rules.

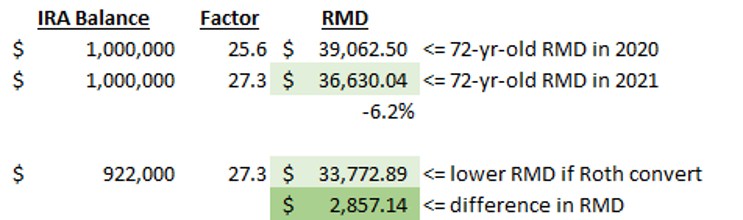

The same rules apply once you turn 72 – first year can be delayed until the following April; subsequent years required by 12/31 of each year. If you delay the first RMD, be aware of income tax hit in second year, as IRA withdrawals count as ordinary income – unless you made non-deductible contributions (check Tax Form 8606). The minimum distribution required equals the previous year-end balance divided by an IRS factor based on age that distribution year. For a 72-year-old in 2020 with a total IRA balance of $1,000,000 on 12/31/19, the factor is 25.6 requiring at least a $39,062.50 distribution. Separate from the SECURE Act, new RMD factors go into effect in 2021. A 72-year-old in 2021 would use a factor of 27.3 resulting in a 6.2% lower required distribution.

This delayed required distribution gives near or new retirees an extra couple tax years of lower taxable income. For some this allows extra years of Roth conversions while ordinary income is lower. It is true that Social Security will have begun no later than age 70 but even two years of a $39,000 per year Roth conversion will reduce the RMD by over $2,800. This is helpful if bumping against the next tax bracket or extra Medicare premium thresholds – or higher future tax rates.

The Ugly: Most non-spouse IRA beneficiaries must withdraw funds out of IRAs over 10 years.

Note this provision does NOT APPLY to the following beneficiaries:

- Beneficiaries of those who passed in 2019 or earlier

- Spouses

- Disabled or chronically ill

- Beneficiaries within 10 years of IRA owner age

- Minor children – though once they reach majority need to switch to 10 years

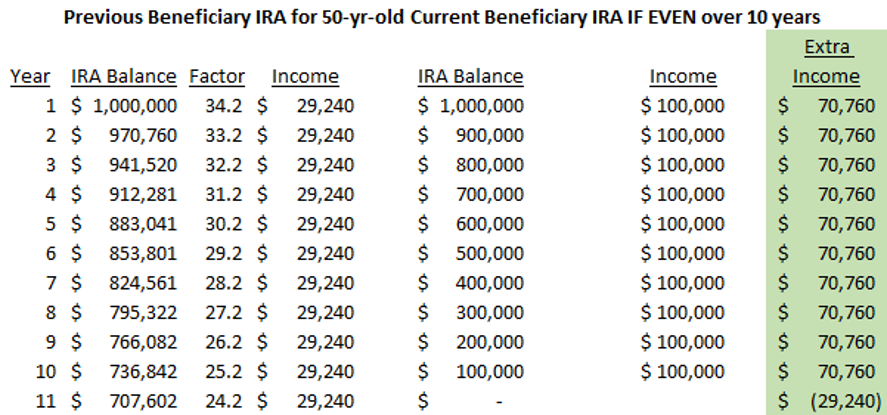

Prior to the SECURE Act, a non-spouse beneficiary was allowed to distribute the IRA based on their own life expectancy using RMD factors from the IRS. For example, a 50-year-old by 12/31 of the year following death of the owner would have used an RMD factor of 34.2. A $1,000,000 inherited IRA would result in first year required distribution of $29,239.77. The factor reduced by 1 each year (different approach for owners) and was divided into the previous year-end balance.

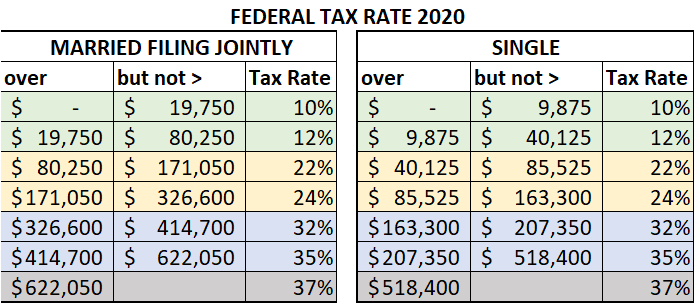

Now when the owner passes that $1,000,000 must be taken by the end of 10 years. While not required, if the amount is taken evenly and assume 0% gain, that is $100,000 each year, over a $70,000 increase. If the Traditional IRA was all from pre-tax contributions, this entire amount is included in ordinary income. Not only will this potentially bump the beneficiary into a higher tax bracket, it could also have other tax impacts - extra 3.8% Medicare tax, limit IRA deductions or contributions, or make ineligible for tax credits.

Also note that inherited Roth IRAs have required distributions. It is true they are not taxable but you still must distribute them, now over a shorter time period. If funds aren’t needed by the beneficiary, the optimal approach is to take the entire distribution in the 10th year to maximize the tax-free growth.

When considering Roth conversions for the IRA owner, one should now consider the tax impact on the beneficiaries due to this shorter distribution period. In the example below, I assumed an even distribution over 10 years (not required to be even). Relative to the previous rules, this results in an extra $70,000 of taxable income that could likely bump taxpayers into a higher bracket. This is especially true for single filers that may see the 32% marginal bracket fairly easily while a joint IRA owner may be comfortably in the 24% bracket or lower.

Let’s aim for some tax savings.

Posted by Kirk, a fee-only financial advisor who looks at your complete financial picture through the lens of a multi-disciplined, credentialed professional. www.pvwealthmgt.com